See here for Brian Reedy’s counterpoint to this essay.

At some point I heard it isn’t polite to discuss religion or politics at dinner. If that’s true – and boy do I hope it’s not true, because these are my two favorite topics – then you should absolutely not bring up this recent article by Antonio Spadaro, SJ and Marcelo Figueroa.

I myself found Spadaro and Figueroa’s thoughts to be insightful and thought-provoking – as the wide variety of responses their article has generated indicates – even if not the final word on the interreligious dynamics of “values voters” presently at play.

In the article, Spadaro and Figueroa posit an “ecumenism of hate” (all quotations are drawn from the article), which they say has brought together extreme wings of both the Catholic Church and Evangelical fundamentalists. The portion of the Church included in this ecumenism is called “Catholic integralism,” which is essentially the view that the state should be subordinate to the Church and, historically, opposed ideas such as popular sovereignty and separation of church and state. Although Spadaro and Figueroa fail to clearly define their terms (a big no-no when I was working on my philosophy degree!), by “Evangelical fundamentalists” they are presumably referring to Protestants, often non-denominational, who subscribe to a literal interpretation of the Bible.

This union between two seemingly disparate groups, Spadaro and Figueroa argue, has become particularly potent in U.S. politics. They point to a variety of people and events in U.S. history that have been shaped and guided by this worldview. As it stands now, this “ecumenism of hate” is marked by a few key ideas: the United States is blessed by God and is therefore good; any number of bad outside forces are attempting to corrupt this goodness; and the world is approaching a final, apocalyptic conflict between good and evil. The authors also point to some of the key political issues uniting these two groups: abortion, same-sex marriage, religious liberty, and lack of concern about climate change. As the piece continues, Spadaro and Figueroa point to several significant ways in which this union influences America’s theo-political culture.

Political-religious validation vs. political-religious motivation

This piece could be read to say that politics and religion have no business influencing each other. However, such a reading would be inaccurate, to say nothing of uncharitable. My reading of the article is that Spadaro and Figueroa argue that politics and religion have no business validating each other. As I understand Spadaro and Figueroa’s point, politics, whether individual politicians or overarching political movements, should not co-opt religious language or imagery to justify its agenda, most especially when said agenda is ultimately incompatible with that religion’s beliefs. Following the same vein of thought, religions should not turn to the political sphere to increase their power in society. Such a process of using one type of power or influence to validate the other ultimately cheapens each of them.

However, I am absolutely not about to say that religion and politics ought not influence each other. Quite the opposite. One need only look at the Civil Rights Movement, the USCCB’s calls for comprehensive immigration reform, or Jacques Maritain’s involvement of the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights to see prime examples of religion providing both motivation and vocabulary to engage a political issue. The difference between these causes and the approach Spadaro and Figueroa warn against is that, while they acknowledge opposition and seek to change it, they do not strive to acquire power in order to forcibly impose their agendas. Conversely, neither do they simply engage controversial topics for the sake of supporting political forces they may see as “allies.”

Critically looking for coherence between one’s political and religious beliefs is of the utmost importance. Subordinating one to the other for the sake of gaining more power does a disservice to both.

Pope Francis poses with Jesuit Father Antonio Spadaro, left, editor of La Civilta Cattolica, and Father Arturo Sosa Abascal, superior general of the Society of Jesus, before a meeting with editors and staff of La Civilta Cattolica at the Vatican Feb. 9. (CNS photo/L’Osservatore Romano, handout)

The Absolutizing Instinct

One of the most intriguing points I find in this piece is its insight into the theological underpinnings of so-called “values voters.” Spadaro and Figueroa push these underpinnings to their natural conclusions and expose the underlying vision behind them.

As the article explains, the worldview uniting these particular wings of the Catholic Church and Evangelical fundamentalists can be described as “neo-Manichaean.” A person engaging this worldview would see everything in black and white. Any given cause, person, event, or idea is either absolutely good or absolutely evil.

Unfortunately for neo-Manichaeans, the world is not so simple.

Part of the human condition, at least in many people I have met, is an innate desire to reduce all situations to black and white, good or bad, right or wrong. William Lynch, a 20th-century Jesuit author, refers to this drive as “the absolutizing instinct.” This tendency to ignore or erase the nuances of situations, people and ideas is essentially what neo-Manichaeans do, either consciously or subconsciously.

Beyond merely being wrong, the absolutizing instinct ultimately leads those who follow it to miss out on so many of the creative tensions of our world. Rather than taking the time to find common ground or build bridges, they declare anyone with whom they disagree, even partially, to be an enemy. Instead of recognizing the possibility of improvement in a challenging situation, they declare it irredeemable. Instead of being able to work within shades of grey, they see only themselves as “white” and everything else as “black.”

When one reduces everything to absolutely good or absolutely bad, one misses the opportunity to critically engage with the world as it actually exists. The real tragedy of this worldview is that it discourages hope and ignores the fact that we are called to cooperate with the grace God pours out on the world.

Shortcomings and Objections

Important as these insights are, this article is not a complete or exhaustive analysis of these groups’ roles in American culture and society. A few significant critiques immediately stand out to me.

Spadaro and Figueroa might be giving practitioners of the “ecumenism of hate” too much intellectual credit. I can’t help but wonder if the members of these groups have thought through, or even care about, their theological and philosophical underpinnings. Instead, perhaps they simply identify more deeply as members of their particular political party, movement, or social group than they do as members of a religion. In this case, they would be evaluating situations in light of their political commitments and then seeking to validate these political conclusions in light of their religious connections. This same critique could be made of religious people on both sides of the political spectrum. To what degree do I, do we, simply use religion to try to validate my preferred political positions? Conversely, how open am I to the challenge the Gospel offers to my political beliefs?

I understand that neither Spadaro nor Figueroa is from the U.S., but a cursory look at the recent history of religion and politics in the U.S. might offer a simpler explanation for the Catholic-Evangelical alliance than the one they offer. I can’t help but wonder if the Catholics integralists and Evangelical fundamentalists haven’t grown closer together simply because they have found themselves sharing the same political camp for several decades now. A simpler explanation of why these two groups’ worldviews have come to look increasingly similar would be that religious leaders seeking increased political influence during the initial rise of the “Moral Majority” and similar groups found a warmer welcome in the Republican Party than in the Democratic Party. Because the GOP was more willing to listen to these religious people’s concerns, the religious leaders of these movements found themselves able to exert the influence they had been seeking. As a result, any leaders from these different religious groups could find themselves sounding and acting increasingly similar after several decades of sharing political space. While this may not invalidate Spadaro and Figueroa’s points, taking the time to understand the historical origins of this alliance may lead to better insight about how and why it functions in the present.

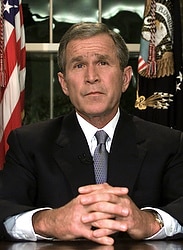

US President George W. Bush is one of the figures accused by Spadaro and Figeruoa of introducing a “Manichaean” element into contemporary US politics. (CNS photo/Larry Downing, Reuters)

Do Spadaro and Figueroa themselves actually fall into a neo-Manichaean absolutizing instinct? In this response, Charles Camosy, a professor at Fordham University, raises the possibility that this is exactly the case. To substantiate his point, Camosy points to the “caricatures” of George W. Bush, Steve Bannon and Donald Trump included in the piece, as well as his own experience in interacting with more progressive Catholics on topics such as skepticism regarding climate change, focusing primarily on abortion in the context of other life issues, and people who voted for Trump. In each of these instances, Camosy has observed a hateful absolutizing instinct at play in attempts to criticize those who Spadaro and Figueroa would include in the “ecumenism of hate.”

I don’t think Camosy’s critique lands, at least in the context of the article he’s responding to. The only references to Bush are his own words and the observation that Osama bin Laden referred to him as a “great Crusader.” Bannon only comes up because he has incorporated some of the world views of some of the figures mentioned in the article. The references to Trump come from an observation of his diction on Twitter, a note that another of the figures discussed in the article officiated at Trump’s first wedding, and then a discussion of how an ultra-conservative Catholic blog covered his election. All of these references strike me as not so much caricatures invented by Spadaro and Figueroa but as direct quotations by the people themselves or about them by obviously extreme sources (bin Laden and Church Militant). Finally, I’m not sure how the lack of civility between liberal and conservative Catholics detracts from Spadaro and Figueroa’s observations.

However, Camosy’s objection raises a critically important question that Spadaro and Figueroa would have done well to address: how do we talk about and with those whose worldviews we find lacking or troubling? If they, or I, were to adamantly label practitioners of the ecumenism of hate as evil, stupid, or intransigent, we would be falling into the same sort of absolutism under critique in this article, to say nothing of denying the possibility of redemption lying at the heart of our faith as Christians. However, pretending that differences in worldviews are inconsequential and thus there isn’t any conflict to be had would be both dishonest and simplistic. It seems to me that the real source of dialogue, and eventual bridge building, comes not from permanently affixing labels on one another, but rather from taking the time to learn more about the other and ask why they hold the beliefs they do. This approach requires an appreciation of nuance, openness to finding points of common ground, and the ability to acknowledge differences.

Rejection of Fear

Even given these objections and shortcomings, Spadaro and Figueroa have pointed out some troubling realities of the current state of religion and politics in the United States, the most pressing of which is offered in their conclusion. This piece ends on a note that is both hopeful and challenging. Much of the ecumenism of hate seems to be driven by instilling fear in its audience. The presentation goes something like this, “X causes disorder. Disorder is scary. Therefore X is bad. We are the opposite of X. Therefore we are good, we will combat and triumph over X, and you won’t be afraid anymore.”

In the final lines of their article Spadaro and Figueroa juxtapose the image of a border fence crowned by barbed wire with the crown of thorns atop the crucified Christ on Good Friday. Poignant though it is, much like the rest of their article, this image, again like the rest of the article, needs to be deepened and extended to fully reflect our identities as Christians. The pain, suffering, and chaos caused by both our contemporary theopolitical situation and the crucifixion can and must give way to the fear and uncertainty of Holy Saturday and the messiness of constructively engaging those with whom we disagree. Only after entering into the tomb and burying our own absolutizing instincts can we emerge into the hope and unity of Easter Sunday.