What kind of conversations are you having as summer comes to an end? Are you still meandering through a popsicle backlog, or on a campus somewhere bristling with new and returning students? Are you talking about hitting a back-to-school and fall sale, or just getting your backyard grill ready for one last Labor Day cookout. Or, just maybe, you’re talking about the risks and benefits of comprehensive prison sentencing reform in the United States.

You’re not? Because that’s just the kind of conversation the office of the Attorney General of the United States may be hoping to provoke. Eric Holder, if you hadn’t heard, has decided to embark on a general reform of federal criminal sentencing. Crime and punishment are governed by laws enacted by Congress, but the executive has a level of what is generally termed “discretion;” that is, the Attorney General and his deputy United States Attorneys, on behalf of the President, can make choices as to what to charge and how strict a sentence to pursue. Holder has decided to be less strict in how this discretion is exercised:

Attorney General Eric Holder is calling on the federal government to rein its use of one of the most ubiquitous tools in the war on crime — mandatory minimum sentences — and he’s making a unilateral move to cut down on such sentences in drug cases even as Congress debates a broader retreat from the once-popular sentencing concept.

“Some statutes that mandate inflexible sentences — regardless of the facts or conduct at issue in a particular case — reduce the discretion available to prosecutors, judges, and juries,” Holder is to say in a speech to the American Bar Association on Monday in San Francisco, according to advance excerpts the released by the Justice Department. “They breed disrespect for the system. When applied indiscriminately, they do not serve public safety. They have had a disabling effect on communities. And they are ultimately counterproductive.”

…

“Certain low-level, nonviolent drug offenders who have no ties to large-scale organizations, gangs, or cartels will no longer be charged with offenses that impose draconian mandatory minimum sentences. They now will be charged with offenses for which the accompanying sentences are better suited to their individual conduct, rather than excessive prison terms more appropriate for violent criminals or drug kingpins,” the attorney general plans to say.

The Washington Post goes on to report that this is part of a broader strategy to reign in out-of-control sentences for low-level criminal offenders, such as nonviolent or elderly offenders.

This comes as many are beginning to question just how effective the US criminal justice actually is. (You may recall my take on the question from a few months ago was generally in favor of such reform.). Clive Crooks at Bloomberg View was quite upfront, noting that the “U.S. Criminal Justice Is a Disgrace.” And The Economist notes that we are experiencing a “curious case” of a fall in crime even as we get tougher and tougher. They see this, like the Attorney General, as a chance to reform our justice systems to focus less on punishment and more on prevention and rehabilitation. And, even if that doesn’t convince you, perhaps the other main motivating factor will: it is just too expensive to continue warehousing so many offenders who might be better served by restorative justice and rehabilitative programs.

Obviously, any change of this magnitude takes time and energy. A healthy, vibrant discussion on how to be approach lawbreakers and criminals is what we need, moving past the simple rhetoric of being “tough on crime” and building more and more prisons. Hopefully, the recent actions of the Attorney General, along with this other recent commentary, can spark just such a conversation.

******

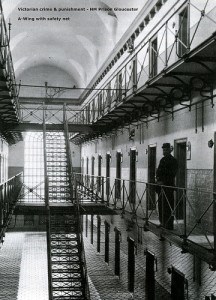

Crime & Punishment photo courtesy Flickr user Paul Townsend