My dad was very amused at the inappropriate level of anger I was showing at the TV screen. He was curious why something like this could stir up such deep emotions in his non-sports-fanatic son.1 But the truth is, one of the more impassioned tirades that I have gone on in recent memory was while watching a baseball game on ESPN with my dad.

The culprit: K-Zone. I am not a rabid fan of sports in general. That said, watching an entire game with K-Zone sent me into orbit.

Just a refresher: K-Zone is the little box that claims to outline the strike zone for batters in all MLB baseball games televised on ESPN. The technology has mostly been used in replays and was developed for baseball and tennis by Ques-Tec in the late 90’s. ESPN’s version of the technology also has a “3D” strike zone that tracks the trajectory of the ball as it crosses the plate.2

As I spent some time looking into K-Zone, I found comfort that my strongly-felt emotions were shared not only by avid sports fans, but also by people who write about and think about sports for a living.

The first reason for my meltdown, which seems to be shared by nearly everyone in the Twittersphere as well as many sports writers, is that K-Zone on every pitch is just annoying. Although it’s not as bad as the glowing puck experiment FOX used in the early 2000s, it’s just unnecessary and distracting.3 The tragedy of Fox-Trax (the glowing “technopuck”) did, however, lead to the creation of the yellow first-down line used in NFL games. This was an actual improvement…like Facebook over MySpace. K-Zone, however, is more like the Google+ of the sports technology world.

But my rant had deeper roots than simply annoyance and historical-criticism.

One of the most time-honored practices in the American sport-watching universe is the practice of thinking that because I am physically or electronically present at a game, I am qualified to play, coach, and officiate any sport, simply by virtue of my presence. We love to second-guess hitters, managers, and umpires. Our universal knowledge of the game doesn’t even stay on the field. We can second guess trade decisions by GMs, penalties levied by the commissioner,4 stadium construction, etc. What gives us the right? I own a television, radio, internet connection, or even a next-day newspaper.

But here’s the deal: that’s part of the experience. What kid growing up doesn’t want to play professional ball? Even me, the music major, imagined his walk-up song and the glory of trotting around the bases after a walk-off home run. And even if our own sports glory days are behind us — or even if they were never too glorious — one of the main reasons we get so passionate when watching sports is that arm-chair managing enables us to participate at a meaningful level.

With the emergence of this new technology, however, that participation is threatened. Far more than just being an annoying yellow box, K-Zone threatens to make us passive, less-invested spectators — and actually eliminate what makes watching sports so enjoyable.5

One of the primary ways we participate in the sports that we watch is by thinking about how we would do things: Would I change pitchers here? Would I call that a strike? Is that the infield fly rule? How can we manufacture a run here?

And how sweet it is when the manager (or hitter, umpire, etc.) does what I would have done!

At some bizarre level, I think we actually care more about whether our decisions match the manager’s decisions. What about the “right call,” you might ask. Who cares! What I would do is the right call, since I’m smarter than all those jokers on the field.

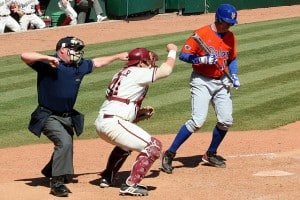

From Mark Barron, Flickr CC

What makes every pitch with K-Zone so insidious is that it subtly removes me from participating in the experience of watching a game. Instead of carefully discerning for myself pitches as they come,6 ESPN just tells me what to think. I don’t have to learn what the strike zone is. I don’t have to learn how to apply it to each batter. I don’t have to appreciate the art of a catcher framing a pitch or a batter altering his stance. I don’t have to know or understand, discern or digest. I just have to sit there passively and see if the ball ends up in the K-Zone box.

Sometimes, after a game with an inconsistent umpire, we see people on TV and social media calling for replacing umpires with technology that would call balls and strikes. Of course, I get frustrated when an umpire doesn’t consistently call the same strike zone from inning to inning or from team to team. But here’s the deal: sports are played by human beings, officiated by human beings, watched by human beings. And expecting consistency from a human being is like expecting inconsistency from a machine.

The human strike zone isn’t just about baseball. It’s about something that is essentially human that baseball, at its best, celebrates: we err; we make mistakes. We can also appreciate nuance, subtlety, and ambiguity. Let’s not forget that the baseball rules themselves allow for things called “errors,” knowing full well that mistakes are part of the game.

The technology that makes K-Zone possible has been used by MLB to help train and evaluate umpires after-the-fact to help them be as consistent as possible. But to use this technology to actually call the game?

Let’s also not forget that a game that embraces the K-Zone reality and the automatic strike zone would also eliminate one part of the game that is as old as Abner Doubleday: arguing with the umpire. Who doesn’t love when, after a questionable call, you see the manager dart out of the dugout to start yelling, red-faced, at the umpire? While the almost histrionic behavior of many managers may not be humanity at its best, at least it is still human.7

For me, K-Zone removes us from the experience of watching a game. It places my own experience of the game beneath a kind of quasi-scientific, cold set of numbers. This data then attempts to trump the beauty and enjoyment of real human experiences. But I won’t let it.

As I sit down to watch this year’s playoffs,8 I will proudly take my place in a long line of armchair umpires, managers, and players and actively engage with the experience in front of me. I’m quite certain I will look foolish shouting at the television, as I did in my parents’ living room. But I will do so happily immersed in the lovely, error-prone mess that is my humanity.