What do you get when you cross Donnie Darko and your Sunday Comics? YouTube channel Gritty Reboots thinks they know. In the current trend of reminiscing about childhood memories, Gritty Reboots has put together a pretty incredible trailer for an (as yet) unmade movie based on 104% of everyone under 40’s favorite comic strip of all time: Calvin and Hobbes.1

The conceit is that Calvin, the six-year-old creator of Spaceman Spiff, has aged into young adulthood. In the trailer, we see how Calvin’s imagination – as powerful as ever, even as an adult – has taken on a life of its own. And a very dark life it is. The figments of Calvin’s imagination that were so wild and compelling and creative (c’mon who hasn’t imagined they were a Tyrannosaurus Rex at some point) now fight to keep Calvin from growing up. Calvin’s increased maturity apparently means their demise, and his imagination has decided to fight back by kidnapping his inestimable partner-in-transmogrification, Hobbes. In order to rescue Hobbes, Calvin will have to confront the darkness that has been growing within him as he has grown into an adult. Take a look.

***

It didn’t take much imagination for me to recognize Calvin’s struggle as my own: the struggle of being forced to choose whether to leave childhood behind or enter the adult world. The two so often seem at odds.

This duel of childhood versus adulthood seems especially vivid when, in an homage to the comic, the trailer presents us with a young, bored Calvin, gazing out across the city landscape. As we watch, his powers of imagination transform the drab city into an alien planet, one that demands to be explored. For me, it’s Calvin’s imagination that characterizes his childhood. It’s not innocence that makes him who he is, but the ability of his mind’s eye to create a world that is full of life and rich with the hum of possibility.

***

After watching the trailer, though, I found myself asking a question: if imagination is the mark of childhood, does becoming an adult mean leaving our imaginations behind? Does it mean entering into that flatland of adult reality where all Martian landscapes go to die? Are all the possibilities our minds conjure up nothing more than that: possibilities, conjurings, tricks, and magical illusions that disappear when the smoke clears? In other words: is the imagination of childhood at odds with the truth of adulthood?

Perhaps the older Calvin’s imagination has just become tainted with the malaise that we call real life. Whether he is or not, it’s this dichotomy, this trope living unquestioned under the bed in the back of our minds, that makes this Gritty Reboot work. In one of the trailer’s best lines this dichotomy is fleshed out with a line from St. Paul. It happens when Calvin admits to the audience that he has “tried to put away childish things,” so that he can live an adult life.

But the trailer takes that line out of context. In its fullest context that phrase is one small part of Paul’s famous discourse on love from 1 Corinthians chapter 13. It reads in part:

Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, but have not love, I have become sounding brass or a clanging cymbal. And though I have the gift of prophecy, and understand all mysteries and all knowledge, and though I have all faith, so that I could remove mountains, but have not love, I am nothing. And though I bestow all my goods to feed the poor, and though I give my body to be burned, but have not love, it profits me nothing…

Love never fails…

When I was a child, I spoke as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child; but when I became a man, I put away childish things. For now we see in a mirror, dimly, but then face to face. Now I know in part, but then I shall know just as I also am known.

And now abide faith, hope, love, these three; but the greatest of these is love.

Whether it does for Calvin in the Gritty Reboot or not, I think it is this notion of love that becomes the true bridge to adulthood – and a robustly imaginative one at that.

An imagination charged by love retains its child-like ability to transform reality while not running from it. While an imagination fueled by the dregs and boredom of life becomes escapist, child-ish and insular, a child-like imagination uses the capacities that accompany adulthood to transform reality for the better. It’s not about seeing a boring city and changing it into an alien planet to explore. It’s about seeing the hope already present in the city and hearing its call to make that hope take new, concrete forms.

***

If I were working with Gritty Reboots, and we were bringing this film to full production, this is how I would end the movie: after traveling through endless hostile landscapes, after battling monsters that would rival those in the Lord of the Rings, after unpuzzling some final puzzle, Calvin would find Hobbes – only to discover that Hobbes had staged his kidnapping himself to lure Calvin on a journey of self-discovery.

In my ending, Hobbes would remind Calvin of their friendship and the love they share, a love so fierce that it compelled Calvin to dive into an imagined darkness he didn’t really understand to rescue his friend.

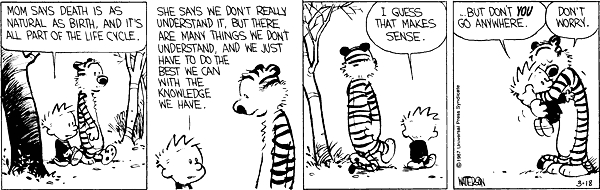

And I’m not completely imagining this. I used the process of writing this as an excuse to dip back into the Calvin and Hobbes archives, and in so doing I rediscovered a favorite old strip, one that depicts Calvin feeling the pain of loss and relying on Hobbes’ friendship. The last panel shows the two hugging, Calvin telling Hobbes, “But don’t YOU go anywhere.” “Don’t worry,” Hobbes replies. It is this kind of loving friendship that allows Calvin – and us – to imagine “a new year, a fresh, clean start.” If we learn the lesson Hobbes is trying to teach us, we don’t have to choose; adulthood only improves with a child-like imagination.

Don’t Worry

– — // — –