It’s the skirt and costume that get me.

See, I want to believe… I desperately want to believe that Wonder Woman (WW) empowers women. I want to believe that she inspires women, showing that they are truly powerful, independent, and heroes. I want to believe that Wonder Woman is not simply a female superhero, but a character who communicates womanhood with all of its complexity, challenges, and possibility.

She certainly has the qualifications. She is as strong as Superman, nearly as fast as the Flash, and as smart as Batman. Wonder Woman is royalty, possessing the poise and power to command. She holds weapons of a different sort, including lasso which wields truth itself. She comes from a world separate; instead of being tied to a nationalist movement, she offers insights into humanity. She moves beyond the values of “truth, justice, and the American Way,” often encapsulating a sort of utopian hope in a perfect world—a world in which people are inherently good and capable of more than even they can image. Wonder Woman, at her core, is a better hero than any of her male counterparts. And, let’s be honest here, she was the only thing saving the Batman VS. Superman movie…

But then, I see the skirt and the costume. At which point, my eyebrow lifts and inevitably think something like, “Yeah… Pro-woman? Right. Sure…” Wonder Woman holds the potential to be pro-woman, but so often seems tied down with the tropes of her male counterparts, or subverted with anti-woman imagery and characterization. If only she were set free to be fully (Wonder) woman.

I’m torn, but that tension is exactly the tension in which Wonder Woman exists and was born.

Wonder Woman from the Super Friends cartoon (Tim Simpson/flickr)

An Origin Stranger Than a Long-Lost Amazonian Island:

Wonder Woman’s comic book origin begins from somewhere strange—an island far removed and alien—but her actual origin is nearly as fantastic. On the surface, she was born in response to the negative attention and critiques of comic books like Batman and Superman. But deeper, she was born from the first wave of feminism and from an author with his own agenda.

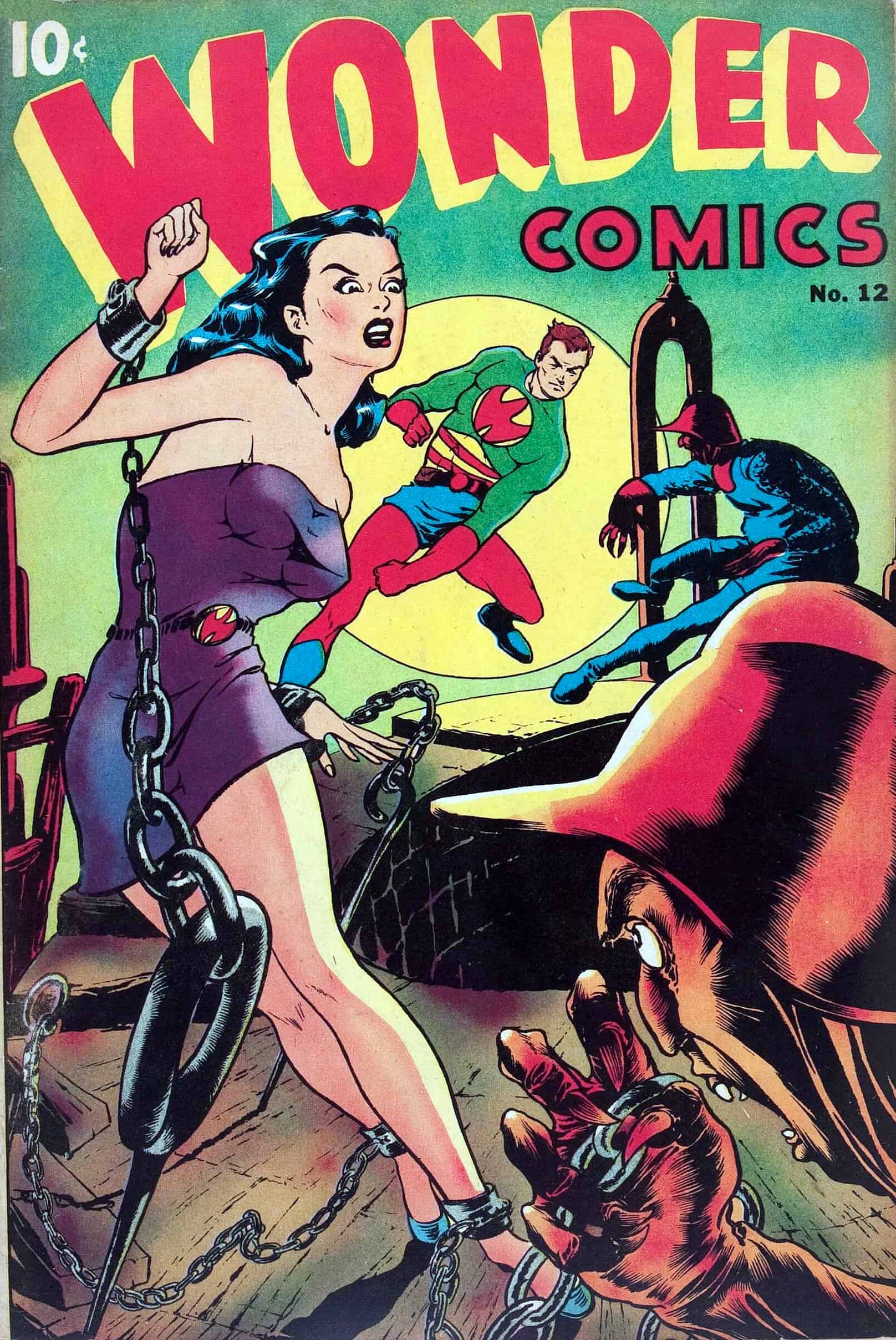

Comic books may have appeared before WWII, but they gained wide popularity in the immediate context of the war. Superman, Batman, Captain America all appear during this time. With their rise though, critics quickly began to express their concern over: the ‘super’ nature of these characters, the vigilante justice, the violence, the overt masculinity and sexism, and even the horrors of the villains. As strange as it sounds today, there were groups and associations founded to “protect the youth” from these dangerous things. And then, Wonder Woman came to save the day! Sort of.

Wonder Woman Comics #12 (Tom Simpson/flickr)

William Moulton Marston created the character of Wonder Woman as a response to the negative criticism, but also to promote his own quasi-feminist agenda. Marston’s background was bizarre; he earned a law degree and a PhD in psychology from Harvard. He worked his way through school writing screenplays for silent movies, but failed to later hold a job in Hollywood. He also considered himself a psychological researcher, and he possibly has a claim to creating one of the earliest “lie detector” tests—which maybe was the inspiration for Wonder Woman’s Lasso of Truth.1 He worked for army intelligence during WWI, and he taught at various universities though promoting his research and theories always came first. Marston’s experiences weave into the character of WW, making her likely the only superhero born from scholarship and academia.

But even more interesting than his background, Marston was an avid feminist, sort of. He was immersed in the front lines of the women’s suffrage movement. His mistress was the niece of Margaret Sanger. He even advocated for a “free love” type of existence long before the second wave began in the 1960s. In fact, Jill Lepore’s biography, The Secret History of Wonder Woman, argues that Wonder Woman could be a bridge between first and second wave feminism. WW presents a continuity moving from the suffrage & rights of the first to the power & independence of the second. Marston himself claims that Wonder Woman was meant as a vision for the future of women:

Frankly, Wonder Woman is psychological propaganda for the new type of woman who should, I believe, rule the world. –William Moulton Marston, March 1943.2

All of this is to say that Marston wrote WW intentionally to promote his vision of empowered women.

Princess Diana could break ropes like that at the age of three. (Tom Simpson/flickr)

This history might lead me to believe that Wonder Woman was in fact pro-woman, but I’m still torn—Marston and Wonder Woman are much more complicated. Marston’s personal history, particularly his love life, is strange. He lived in a semi-polyamorous relationship with two wives who may or may not have had a romantic relationship with one another. One wife had a career, and the other raised the four children. Additionally, his experiments—which were based on theories he attempted to promote within the Wonder Woman comics—were highly sensual in nature and, quite frankly, often just odd and weird. His theories of submission creep into Wonder Woman depicting WW often chained or being subjugated, for which he and the early comics received quite a bit of criticism.

But again, the costume? Well, here again my head tilts, and I simply can’t say that it’s pro-woman. Marston designed WW’s costume specifically after the “Vargas girls”3 which appeared in Esquire. It objectifies the female body more than empower the woman, and it seems that the artwork was more for male viewership than for female empowerment or liberation.

An Alberto Vargas-drawn advertisement (Isabel Santos Pilot/flickr)

But, Marston did create a different sort of superhero with Wonder Woman. She is much more compassionate and caring as a hero. She often finds her agenda or mission in assisting women, children, and the vulnerable. WW was less violent than her contemporary male counterparts, and she is much more optimistic and hopeful concerning humanity. Also, many of her plots take place on a college campus—often promoting women’s higher education. She is simply better than her counterpart superheros—that is of course, when she is left to be Wonder Woman rather bottled for male consumption. What Marston did right was to construct her differently than her male counterparts—she much more than just a female superhero. What he did wrong, at times, was to tailor her and her feminism too much for men, undercutting her power as a woman. Marston wasn’t alone in this failing.

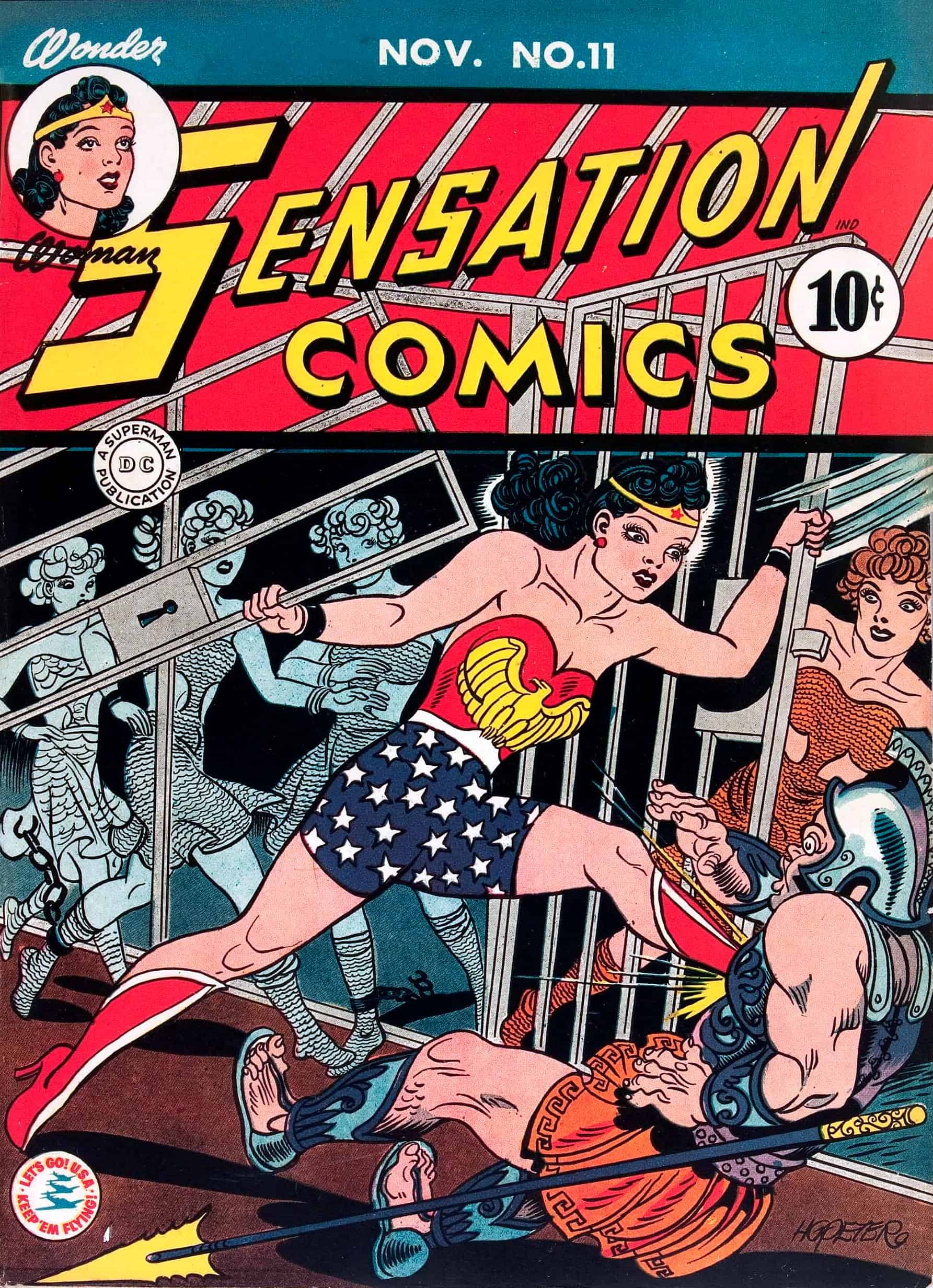

Marston died only a few years after creating Wonder Woman. While his wife volunteered to continue the WW comics—rightly claiming that she understood the woman and character—Wonder Women was handed over to the control of men. Marston’s legacy, his version of Wonder Woman as a better hero, quickly faded away. She simply became a female version of Superman: just as violent, less compassionate, less unique. There was even a bit of time during the “Diana Prince years” where Wonder Woman lost all her powers and became a secretary and a wife. Her role in those comics: to promote a domestic ideal of a woman.

Wonder Woman’s history struggles with the tension between being Pro- or Anti- woman. At her best, she empowers; at her worst, she undercuts. But, where does the newest incarnation of Wonder Woman fall in the Pro- vs. Anti- debate?

Wonder Woman: A Different, Better Hero:

I’m no stranger to superheroes and superhero movies, and, frankly, Wonder Woman is my favorite movie and hero. Gal Godot’s WW is an empowered woman, whom I admire much more than Superman or Batman. She not only represents a better superhero, but she represents a different sort of character than what we usually see in superheroes.

The movie opens with Wonder Woman walking into the Louvre in Paris. Gal Godot’s WW is elegant in nearly every way, but further she’s obviously brilliant. Seeing her in the Louvre, the viewer must assume that she is at the top of her field—and the ornamentation of her office confirms it. Our first view of WW is of a woman, radiant, graceful, and academic.

Gal Gadot as Greek-Goddess Wonder Woman (Warner Bros.)

Wonder Woman’s costume still reveals, but does so differently. As opposed to the Vargas Girls or pin-ups, this costume mirrors the uniforms of ancient Greek warriors. In a scene wherein Wonder Woman must choose a “plain clothes” costume in order to blend into the world, she obviously favors some combination of beauty and practicality. She tears a dress, asking “how do you fight in this?” What she eventually chooses not only highlights Godot’s beauty, but it allows for her movement and even allows her the ability to hide her weapons and WW costume below. What’s notable about the scene is that the choice of uniform rests completely with WW. What does she does with that choice? She chooses her own balance of elegance and power, rather than allowing someone to dictate it for her.

Gadot’s character possesses a sort of naivety and innocence. Instead of this being off putting, it demonstrates a conviction simply better than other heroes. Wonder Woman in the movie believes that all people are naturally good. Her view of humanity even drives the plot where she believes that if she simply defeats Ares all will be well—humans will return to a utopian world of love. Naïve? No—magnificent. Her interactions with Steve Trevor (her love interest played by Chris Pine) reveal her idealized love; she holds a hope which heroes and even humans have lost. She believes in humans. She, in fact, rejoices in them and celebrates them. Further, of all the superheroes, she seems genuinely to love them.

We see this love in two powerful scenes in the movie. In one, as she and Steve make travel arrangements, they meet wounded soldiers from the front of WWI. Wonder Woman is noticeably disturbed by the suffering and the pain. Unlike other (male) superheroes who turn this into a sort rage and revenge motivation, she openly reflects at the horror of it all. Godot’s performance communicates compassion and care in ways we do not see in Batman or Superman. It’s not a “feminine” moment though—as in, this isn’t simply a stereotyped emotional response—but her response is “better” than her peer heroes. Unlike the others who hold themselves separate, she encounters the pain, suffering, and reality of people.

That genuine encounter drives Wonder Woman with an ideological certitude: she knows and feels what’s right. She chastises the commanders of the British in WWI claiming they have no courage or understanding. When she meets a refugee in a trench, she immediately crosses the no-man’s land to save the woman’s village. Where jaded Batman would subvert the system and work in the shadows to fix the problem….where alien Superman would be the messiah offering a model for humans to immolate… Wonder Woman instead encounters and empowers the people to see the truth and to love.

Gadot’s Wonder Woman represents the best of us, not simply the best of women or the best of superheroes. She loves, she hopes, and she acts with those traits as her motivation.

Sensation Comics #11 (1942) cover by H. G. Peter (Tim Simpson/flickr)

Which leads me to the question: Is Wonder Woman Pro- or Anti- Woman?

Certainly, Wonder Woman has a complicated origin. She was written to be a different sort of hero, but has often existed in a tension. While she could empower women and humanity, many of her incarnations either undercut women’s empowerment or lack any distinction from their male counterparts. Thankfully, Wonder Woman succeeds where her predecessors have failed. The women behind the Wonder Woman movie deserve recognition: Director Patty Jenkins’s for her leadership and insight, and Gal Gadot for her depiction of interwoven grace, beauty, power, and compassion.

Maybe, finally, Wonder Woman has been freed to be Wonder Woman. At last she’s free to be more than simply a female hero. At last she’s free to show us a better hero. At last, WW is free to show the power of woman—representing the best not just of women but of all humanity.