“Jaret, ¿estás disponible para acompañar a estos hermanos?”

On June 25, 2021, I was working in the reception area at Kino Border Initiative,1 a migrant aid center on the Mexican side of the border, when our social worker called me over to help two brothers from central Mexico. They were looking for help finding their brother, a 35-year-old father of two, who had attempted to cross the border at a remote location in the desert about two weeks prior. They had lost contact with him, but someone from the group he crossed with said he was injured and left behind on the hillside.

Over the next several hours, we worked to create a more detailed timeline with people in his group. We contacted the Mexican consulate and various law enforcement organizations. Eventually, we were able to pinpoint the exact GPS location where he was left by surveying a fellow migrant’s 15-second video of the mountains and comparing it with Google Earth.

The phone calls made to officials that day were frustrating for us, repeated dead-ends. One volunteer group, Battalion Search and Rescue,2 returned my calls, which led to a partnership that has grown over the past three years. In that time, we’ve walked hundreds of miles in the remote desert borderlands of Arizona in search of the lost but not forgotten. Together, we have found dozens of people, both dead and alive.

There is a hidden crisis of disappearance.

Since 2007, the remains of over 3,000 people who have died while crossing the border have been found in Arizona alone.3 This number does not come near the true number of deaths, in part because not all counties share their statistics but also because the desert rapidly erases people. Some forensic anthropologists I have spoken with suggest for every person’s body found, there are five that remain unrecovered.

There is nothing “natural” about thousands of people disappearing in the desert. The phenomena of death and disappearance only began after the introduction of the “Prevention Through Deterrence” strategy enacted in the 1990s along the southern border. The government strategy is to push migrants away from urban areas, such as San Diego or El Paso, and into more remote, hazardous border regions. A congressional report released in the late 1990s states that: “The overarching goal of the strategy is to make it so difficult and so costly to enter this country illegally that fewer individuals even try.”4 This strategy has not deterred undocumented border crossing. The root causes of extreme poverty and violence remain untouched. However, it has had the effect of making the crossing more expensive, raising the profits of cartels, and also more deadly. The relatively rare occurrence of death in the desert is now commonplace. In the meantime, families of those who die are often left without any knowledge of what happened to their loved ones.

Christian history- Corporal works of mercy

The works of mercy have held pride of place from the earliest Christian communities. Jesus lists out what are now considered by the Catholic Church to be the first six “corporal works of mercy” in Matthew 25:31-46. The seventh, burying the dead, was a hallmark practice of early Christians. Early Christians did not only bury members of their community but also any outcast or poor person who had no one to claim them. One Christian author wrote at the beginning of the 4th century that:

“We will not therefore allow the image and workmanship of God to lie as prey for beasts and birds, but we shall return it to the earth, whence it sprang: although we will fulfill this duty of kinsmen on an unknown man, humaneness will take over and fill the place of kinsmen who are lacking.”5

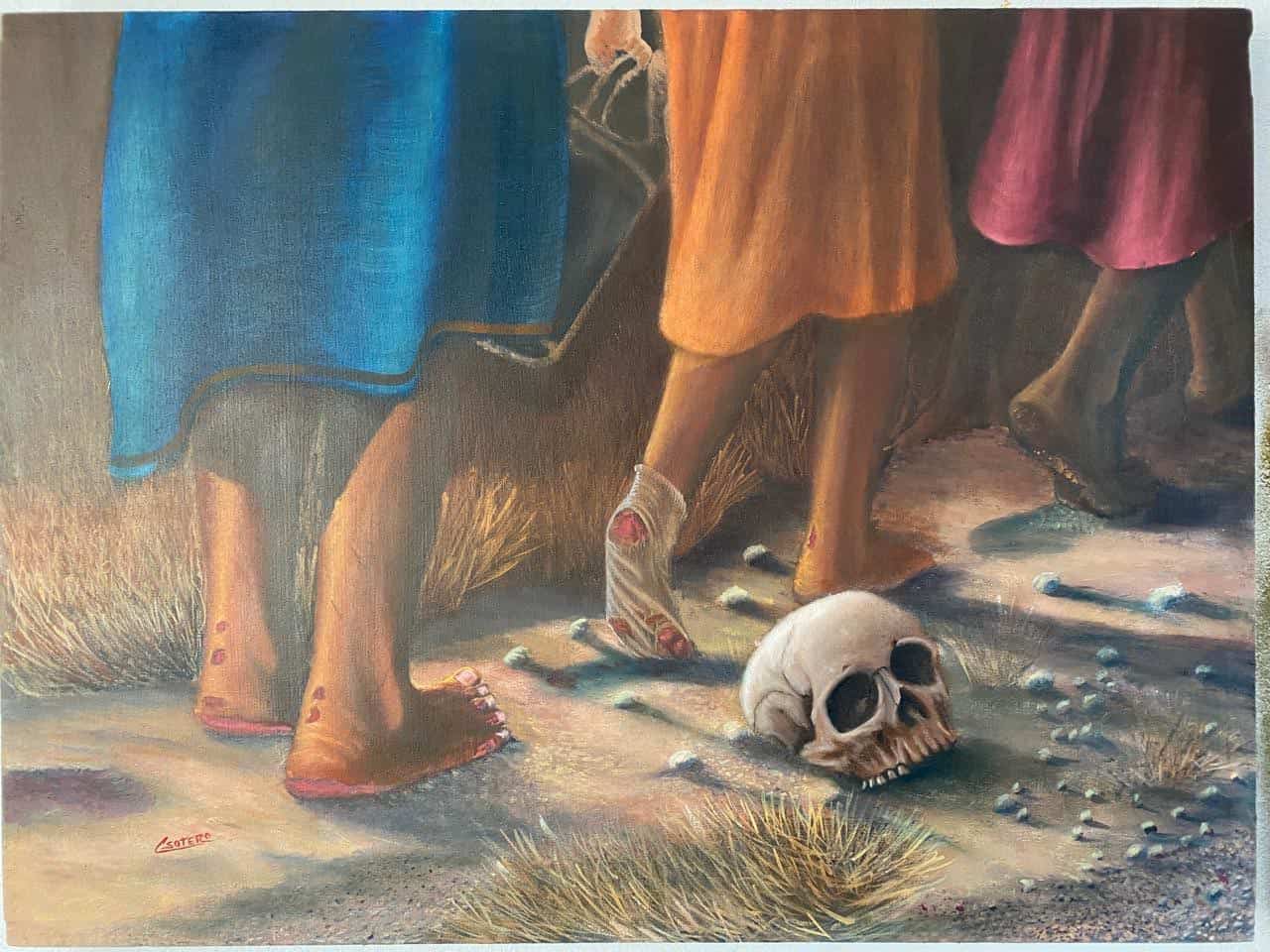

Before going out into the desert, I had never practiced the seventh corporal work of mercy, burying the dead, outside of attending funerals for relatives, friends, and fellow Jesuits. On the July morning of my first search, I felt the weight of this work. Our group of 25 volunteers was out on a live Air Force bombing range with a military escort. The temperature was rising toward 117 degrees that day, so it was imperative to start at dawn and finish by noon. We walked for miles in a baked and burnt open desert where ancient lava flows had broken the crust and hardened on the landscape. Throughout the morning, we passed bombed-out aircrafts and the rusted remains of missiles and high caliber shells. By the time we finished, we found two sites with single human bones, but these bones had been in the desert for over a year. The person recently abandoned by his group was still missing.

Spiritual fruit of this work

While hiking in remote mountains and deserts is a physically demanding task, I consider the search and rescue work a dual spiritual task of providing dignity to those who have died and closure to their families. While trekking the miles, I usually pray a rosary for the dead, their families, and for my fellow volunteers. When we find remains, after marking the area with high visibility tape and taking the GPS location, we often take a moment of prayer and silence to acknowledge the life lost.

As a Jesuit, this work feels like a lived experience of the Third Week of Saint Ignatius’ Spiritual Exercises, accompanying Jesus in his Passion. St. Ignatius invites us to stand before the Cross and not turn away from the pain and injustice. Yet, as Christians, we do not believe sin and death have the final victory.

We have been able to take part in rescues that have been nothing short of miraculous. And while I have felt the weight of death in the desert, there have also been moments where I have felt God’s consolation break through. Last December, as I walked, scanning the creosote shrubs for bones and praying for the dead we had already found that day, I felt an unexpected rush of comfort. Words fail, but it was like a glimpse and an assurance that the Lord had welcomed them home. I continued to walk, still silently scanning with tears running down my cheeks.

Photo Courtesy of Jose Luis Sotero

The post Searching for the Lost but Not Forgotten in the Borderlands appeared first on The Jesuit Post.