At a Jesuit community dinner last week, an older Jesuit priest inquired about my recent summer travels. When I told him I had just returned from the 10th National Eucharistic Congress in Indianapolis, without a beat, he responded: “Oh yes, the Catholic Woodstock.”

“Yes, er… something like that,” I responded.

Whether it is appropriate to juxtapose the traditional Catholic piety and devotions of the NEC with the rock ‘n roll and revelry of Woodstock is an open question. These two mega-events certainly have similarities. As Woodstock was for the 60’s counterculture movement, so was the recent Congress hoped to be for Eucharistic revival in the U.S. Catholic Church.

There were differences, of course: Instead of psychedelic drugs, participants consumed the body and blood of Christ; over 200,000 hosts and 12 cases of wine were consecrated during the five-day gathering. Rather than the smell of marijuana, there was an ever-present aroma of incense. Instead of fans cheering on pop icons, we witnessed a congregation equally devoted to silent prayer and the joyful sounds of praise and worship.

All the heavy hitters were there—not quite Jimi Hendrix, The Grateful Dead, and Janis Joplin, but the U.S. Catholic world’s own spiritual celebrities: the Rev. Mike Schmitz, Bishop Robert Barron and Miriam James Heidland, S.O.L.T.

But just as Woodstock was missing Bob Dylan and the Beatles, the Eucharistic Congress seemed to be missing an important voice. Where were the Jesuits?

Well, technically, the Jesuits were there. Robert Spitzer, a Jesuit priest, was a speaker. Several of our high schools, including St. Xavier in Cincinnati and St. Ignatius in Chicago, sent groups of students and teachers, and other Jesuits came on their own to promote vocations or to cover the event. But there did seem to be something lacking in the Jesuit presence. Why not more Jesuit voices among the 157 speakers? Why not a greater student presence from our 27 colleges and universities? Why not a more visible footprint from other Jesuit ministries?

When I chose to attend the Congress, I had a sense that the Jesuit presence would be somewhat thin. I sensed—along with my companion Eric Immel, S.J.—that there might be skepticism, hesitation, or even antipathy toward the Jesuits among many of the attendees. My hope was joyfully to represent the Society of Jesus in that space, showing that we, too, love the Eucharist.

What I discovered was that the Jesuit contribution and charism at the Congress was indeed present—it was simply hidden. In particular, my experience at the Thursday morning Mass celebrated by Cardinal Timothy Dolan in Lucas Oil Stadium showed that St. Ignatius and the spirituality he developed, though not explicitly mentioned, was definitely present in ways that affected everyone at the Congress.

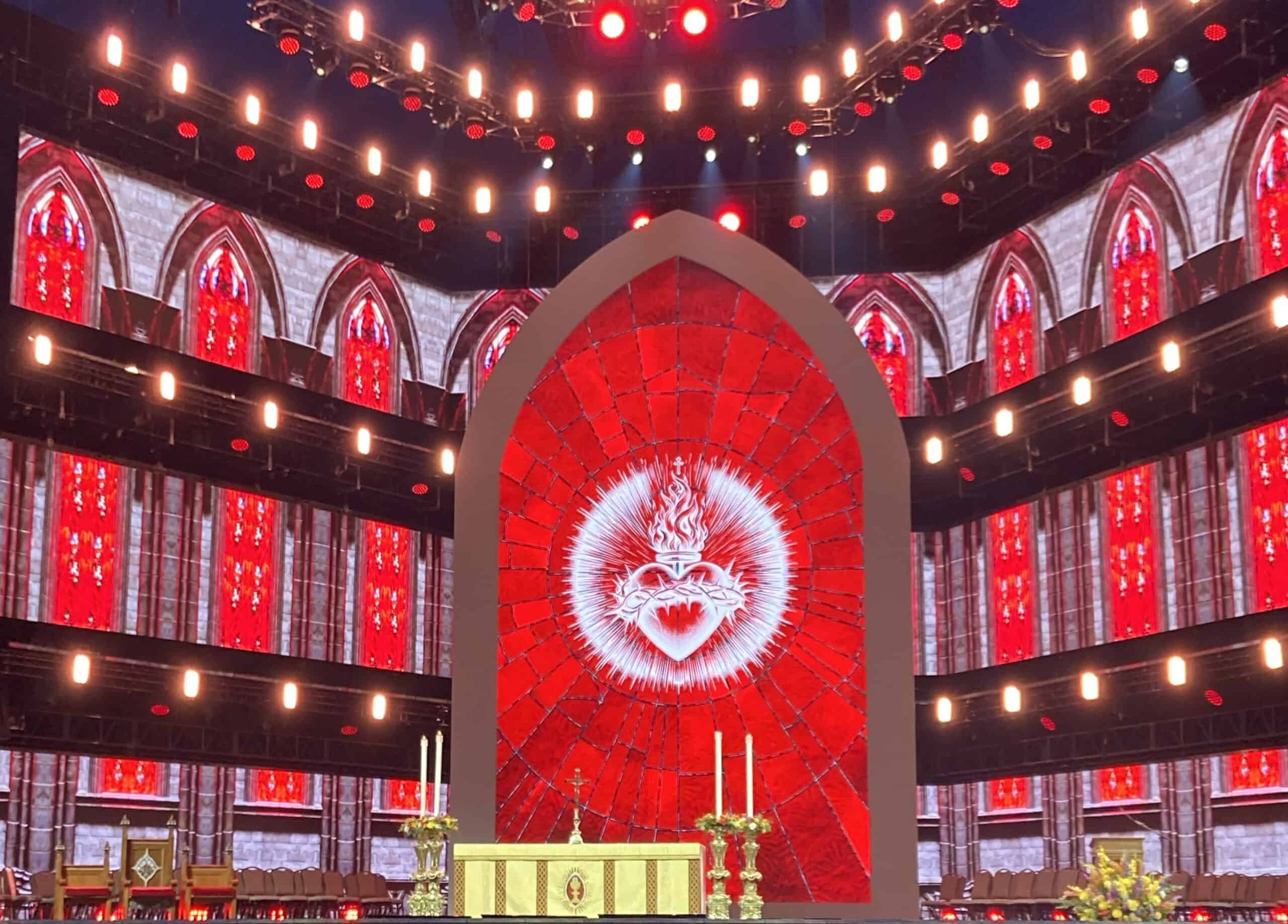

When I processed for Mass in the large arena that morning with a few hundred other seminarians, I was immediately struck by the large projected image of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in the apse of the sanctuary. The image was a brilliant shade of red, and it could not help but draw the eye of everyone. My heart surged. The Sacred Heart is, after all, a devotion that is specifically entrusted to the Society of Jesus, its origins traceable to St. Margaret Mary Alacoque and her Jesuit spiritual director, St. Claude la Colombiėre.

A few minutes later, as I listened to Cardinal Dolan preach in his homily about the heroic and saintly example of Walter Ciszek, S.J., my spirit soared higher. He spoke of Father Ciszek’s devotion to the Eucharist even in the horrific and scarce conditions of the Soviet gulag. Though it was not specifically mentioned, Ciszek was a Jesuit— his very presence in that part of the world initially was thanks to a mission given to him by his Jesuit superior. Moreover, his resilience and determination in the face of his long and tortuous imprisonment were possible in large part due to his intense Jesuit training.

Later, during the communion meditation, the musicians led the congregation in the medieval chant “Adoro Te Devote.” While the authorship of that hymn belongs to the Dominicans—specifically, to the great St. Thomas Aquinas—the beautiful and poetic English translation that we sang immediately following, which is commonly used in parishes all over the country, was written by the English Jesuit poet, Gerard Manley Hopkins. The lyrical lines of Hopkins’s translation, which address the prayer to “Godhead here in hiding, whom I do adore,” allowed the 99 percent of those gathered who had not mastered Latin to enter more fully into the mystery of the Eucharist which we were celebrating.

Finally, the Mass concluded with a musical rendition of the “Anima Christi” prayer, which begins, “Soul of Christ, sanctify me. Body of Christ, save me…” This prayer—written by an unknown medieval author—was popularized by St. Ignatius thanks to the prominent place given to it in his Spiritual Exercises. In most print versions of the Exercises, the “Anima Christi” appears on the very first page. Ignatius asks anyone undergoing the retreat to return to this prayer at various moments, especially when concluding a colloquy, or conversation, with Jesus.

Devotion to the Sacred Heart, the life of Walter Ciszek, the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins, and the “Anima Christi”—all Jesuit influences on the Congress.

St. Ignatius often referred to the order which he founded as the “least Society” (minima compañia) of Jesus. Jesuits today often repeat this expression, but with their tongue in their cheeks—for they know that their order is one of the largest, most influential, and most well-resourced religious orders in the world. Yet, disappointed as I was not to see a greater presence of my order at the Congress, it was somehow fitting for the Society’s influence at the Eucharistic Congress to be more in line with the minima compañia of Ignatius’s original vision. We are here to serve the Church, not be served by it. I sat, stood, and knelt among my fellow seminarians, consecrated religious and diocesan, during Masses with a humble and grateful heart, knowing that Jesuit contributions to the church were indeed highly represented at the congress—whether or not it was known or made explicit.

The post The hidden ‘presence’ of Jesuits at the National Eucharistic Congress appeared first on The Jesuit Post.